Learning With AI, Not Around It

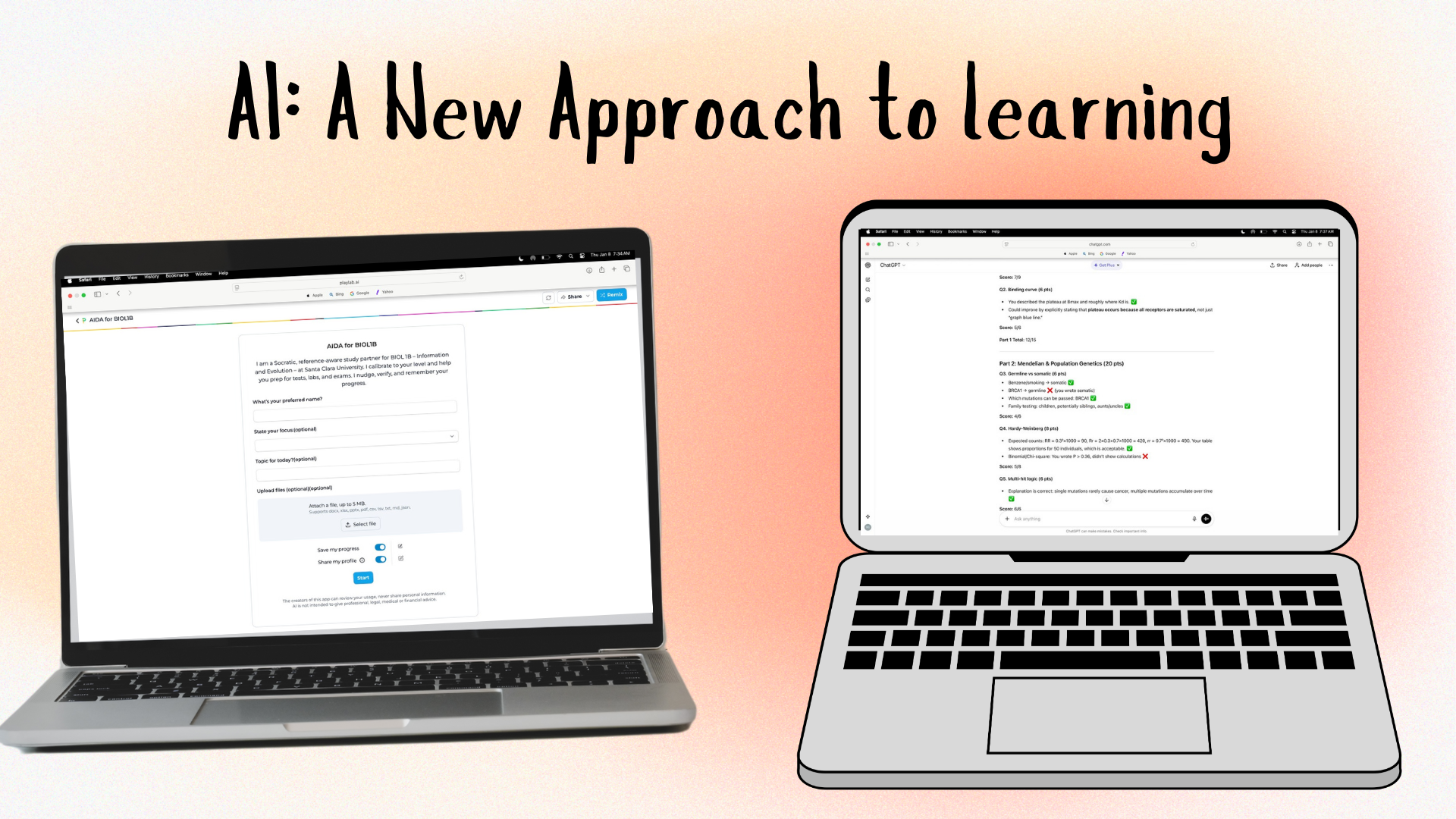

(Graphic by Angela Hansen and Giorgio Lagna)

For many students at Santa Clara University, artificial intelligence, or AI, has become a quiet presence in academic life. It shows up late at night when deadlines pile up, when lecture notes stop making sense, or when it is unclear how to begin an assignment. But despite how common these tools have become, their use often feels uncertain. Is this allowed? Is this cheating? Is everyone else doing this and just not saying it out loud?

For Angela Hasan ’28, that ambiguity has been stressful. Different professors offer different guidance, ranging from outright bans to vague permission. The result is not clarity, but confusion. Many students end up using AI secretly, even when their goal is not to cut corners but to understand the material more deeply. When expectations are unclear, honesty becomes risky.

At the same time, pretending AI does not exist is unrealistic. These tools are already shaping how students read, write, study and solve problems. The real question is not whether students are using AI; it’s whether or not they are using it well.

That question matters just as much to faculty. For Santa Clara University biology professor Giorgio Lagna, the rapid rise of AI has forced a reckoning with long-standing teaching practices. Academic integrity has been enforced through policing for years. With AI, that approach breaks down quickly. Detection tools are unreliable, and enforcement erodes trust.

More importantly, policing misses the point. The deeper challenge is not how to stop students from using AI, but how to design learning experiences where AI use strengthens understanding rather than replaces it.

In BIOL 1B, a lower-division biology course at the University, the two authors occupied both sides of the classroom. Lagna taught the course. Hasan took it as a student. That shared experience created an unusual opportunity to compare notes in real time about how AI was actually being used in practice.

In this course, Lagna introduced an optional AI-based Socratic tutor called AIDA. The tool was designed to ask questions back, guide reasoning and help students test their understanding without supplying answers outright. Because its use was supervised rather than anonymous, some students were initially hesitant to engage with it regularly, despite clear expectations.

Hasan entered BIOL 1B as a sophomore majoring in biology with a minor in public health. As a first-generation college student, she initially found STEM courses especially challenging, not because of lack of effort, but because learning how to study effectively and prepare for exams was itself unfamiliar. Early in the quarter, she used AIDA occasionally to clarify difficult concepts that did not always click during lecture. While it helped her understanding, she still struggled to feel confident during exams.

Adapting to exams conducted digitally on Google Docs, along with the pace and depth of the material, contributed to underperformance on the first exam. With support from her instructors and an opportunity to improve on later assessments, Hasan decided to change her approach.

Using the course’s published learning objectives and prior exam formats, she began creating AI-assisted mock exams. She completed them under timed conditions, then used AI feedback to identify gaps in understanding and revisit weak areas. These mock exams were not shortcuts. They mirrored the structure and reasoning expected on the actual assessments and required active engagement with the material.

The results were noticeable. Hasan’s exam performance improved steadily across the quarter, even as each assessment became longer and more conceptually demanding. More importantly, her confidence and material understanding improved. Using AI as a tool, she entered later exams understanding not just what she knew, but why.

Student feedback at the end of the quarter echoed this experience. Several students described AIDA as a tool that helped them identify gaps in their understanding, shifting their studying away from passive rereading and toward more active, focused engagement with the material. Many also noted that it made the process of studying feel less overwhelming.

At the same time, several students admitted they were hesitant at first, unsure whether using AI, even when explicitly allowed, might cross an unspoken line. That hesitation reveals a deeper issue. Students are not only worried about grades. They are worried about doing the wrong thing in an environment where expectations feel inconsistent.

Lagna responds by removing that ambiguity, explicitly defining where AI is appropriate and how it should support learning rather than replace it. That commitment to clarity has shaped how he designs courses beyond BIOL 1B. In his upper-division genetics classes, he assigns recent research papers that are far beyond what students could decode on their own. With structured guidance and AI support, students work to understand the background, simplify complex methods and present the science to their peers. AI becomes a scaffold, not a shortcut.

In non-major biology courses, Lagna redesigned research projects as multi-step processes that explicitly incorporate AI at specific stages. Students use AI to brainstorm, refine explanations and adapt their work for public-facing formats such as websites or social media campaigns. The final products require students to make substantive decisions about content, framing, and accuracy, emphasizing judgment, creativity and accountability.

These experiences point to a broader issue at the University. Innovation is happening, but unevenly. Students encounter very different AI expectations from one class to the next.

This is where Santa Clara University has an opportunity. Instead of allowing AI expectations to vary widely from one course to the next, the University could offer a common framework for AI use that instructors interpret within their own pedagogical goals. Shared guidance would reduce student confusion while encouraging transparency, experimentation and trust.

Students also have a role to play. The question should not be “Can I use AI?” but “How can I use AI to think better?” That shift requires openness, not secrecy, and a willingness to ask for guidance rather than hide uncertainty.

AI is not going away. The choice facing universities is whether students will navigate AI quietly on their own, or learn to use it openly within the classroom. If Santa Clara University wants to prepare students for the world they are entering, the classroom is the place to start.